At the 43rd Annual Marion Thompson Wright lecture series last week, scholars and activists from Rutgers-Newark and beyond convened to explore links between the food justice movement, which seeks to make nourishment accessible to all, and the cultural legacy of Black culinary traditions.

Newark Mayor Ras Baraka and Senator Cory Booker also addressed the crowd of more than 600 in-person and online viewers, with Booker taping a video message for the series, which was titled , “Beans, Greens, Tomatoes: Food Accessibility and Justice in the Black Diaspora.”

Jack Tchen, professor of history and director of the Clement A. Price Institute on Ethnicity, Culture, and the Modern Experience, which sponsors the series, opened by describing the abundant wildlife in northern New Jersey before it was colonized and the Leni Lenape were driven away, including oyster beds with shellfish that measured 18 inches.

“It was one of the most biodiverse areas anywhere in the world,’’ he said, drawing a connection between environmental destruction and food scarcity in cities like Newark.

“What does it have to do with what we’re talking about today?” he asked. “Everything. We’re talking about food justice and the simplicity of food, what happens at the kitchen table…We have enough food to share, why is it not accessible to everyone?”

He added, “There are other questions that aren’t about justice but deliciousness, and what traditions does that come from?”

Rutgers-Newark Chancellor Nancy Cantor also emphasized that what we eat, and how we get our food, is a global issue that’s also deeply personal. “Our discussions today will persistently remind us that food – culture, sovereignty, accessibility, sustainability – is a matter of collective action, an “emancipatory discourse”, as the scholar Bobby Smith frames it,’’ Cantor said. “It is also a matter of personal significance that in many ways, some subtle and some obvious, define our own individual stories and identities, framed against the background of a globalized food system.’’

The featured speakers, all well-known authorities on food traditions of the African diaspora, stressed that the creative genius of Black culinary history is a defining feature of America, especially in the case of New Orleans cuisine, which has been shaped by Black chefs.

“For more than two centuries, they’ve said the food in New Orleans is the singular achievement of american culinary accomplishment…Africans are largely responsible,’’ said author Lolis Eric Elie, a New Orleans writer and food critic, author of “Smokestack Lightning: Adventures in the Heart of Barbecue Country” and “Treme: Stories and Recipes from the Heart of New Orleans.”

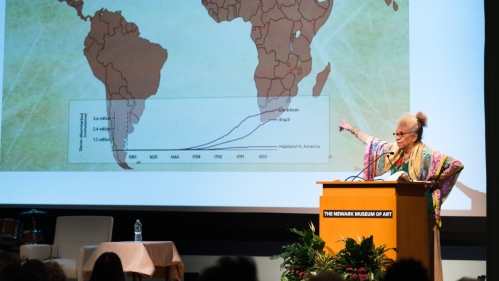

Legendary culinary historian Jessica B. Harris, author of New York Times bestseller “High on the Hog,” the basis for the acclaimed Netflix series, discussed the connections between African and carribean food traditions and the recipes of African Americans. She noted that deep frying in oil and recipes made with codfish, okra and red and black beans have their origins in Africa but are common ingredients for Black people everywhere.

Edda L. Fields-Black, a specialist in the trans-national history of African rice farmers and enslaved laborers on rice plantations in the South Carolina and Georgia low country during the antebellum period, talked about the farming and cultivation techniques that enslaved people brought with them from Africa. These became the foundation for the lucrative industry of southern rice production, even as so many perished from illness, starvation and abuse, she said.

Psyche Williams-Forson, author of” Eating While Black: Food Shaming and Race in America” and “Building Houses out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, and Power,” urged an end to stigmatizing Black people and their diets under the guise of wellness and medical advice.“Food is not killing Black people. Systems are killing Black people, systemic racism. People don’t have houses, don’t have land. Grocery stores aren’t a panacea, but in this day and age, if you don’t have that, that makes it harder,’’ she said.

“It’s not our kitchens that are unhealthy but our souls are weary and tired,’’ she said.

She closed her talk with a piece of advice: “When you are inclined to worry about us, ask us first what we want, what we know, who we are. Otherwise, you should worry about yourself.’’

At the event, onstage speakers and audience members alike were invited to share a memory about food.

Baraka told the crowd that his mother, Amina Baraka, made Hoppin’ John, a recipe of rice and black-eyed peas, every New Year’s Day, a tradition among many Black families in the U.S. “Our culture, while it’s deeply African, is incredibly American,’’ he said.

He explained that food scarcity in cities was the result of a long history of policies in America that are intertwined with redlining. “When we think of redlining, we always think of housing and property but it also had a lot to do with our access to healthcare, the building of medical centers and the building of supermarkets. They purposely built them further away from our communities, deliberately and intentionally as policy. This is not just accidental or because people want to eat bad,’’ he said

Last year, the mayor announced the creation of the Nourishing Newark Community Grants Program, which provides millions of dollars to community based organizations to combat hunger and food insecurity, an effort that was praised by Cantor.

She also recognized Booker as lead sponsor of the Justice for Black Farmers Act, which addresses longstanding federal discrimination that caused Black farmers to lose millions of acres of farmland and robbed them and their families of the inter-generational wealth that land represented.

Several speakers at the event paid homage to the late Clement A. Price, a Rutgers-Newark historian and one of the founders of the Marion Thompson Wright lecture series.

As a first-year at Rutgers-Newark, Lacey Hunter, interim associate director of the Price Institute, was in one of his classes. “He had a unique way of wrestling with questions of the past as if they were still important to our moment,’’ she said.

Hunter recalled a lesson learned from Price and how it guides her own work as a professor. “Black history is made and lived through our every day lives, in ways that produce culture and community,’’ she said.

Jacqueline Mattis, Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences-Newark, said efforts to reduce food insecurity in the city and on campus, were emblematic of Rutgers-Newark’s mission.“An education should be responsive to, and responsible for, the space that we are living in,’’ said Mattis. “How do we shift the everyday work of classes and the way what we think about the life of the mind so that students are engaged in meaningful ways in solving real problems?’’

“It means solving problems around food injustice,’’ she said. “We can do that and we are doing that.’’

Several state and national historians and activists were honored at MTW. They include Jazmin Puicon, Assistant Director of History/Teacher of Social Studies; Bard HS Early College, Newark, and the Ocean County Historical Society. The recipients of the Green School Award were Philip's Academy Charter School and Avon Avenue School. There were also special tributes to Chef Leah Chase, author, chef, TV personality, and co-owner of the historic Dooky Chase Restaurant in New Orleans and Rudy Lombard, New Orleans Civil Rights activist and author of "Creole Feast: Fifteen Master Chefs of New Orleans Reveal Their Secrets.’’