Faculty Member's Milestone Book on Everyday Activists of The Civil Rights Movement Celebrates 30th Anniversary

Thirty years ago, Rutgers-Newark researcher Charles Payne wrote a book that redefined the history of the civil rights movement, shifting the focus from a handful of charismatic leaders to the ordinary people who risked their lives to do the day-to-day work of organizing.

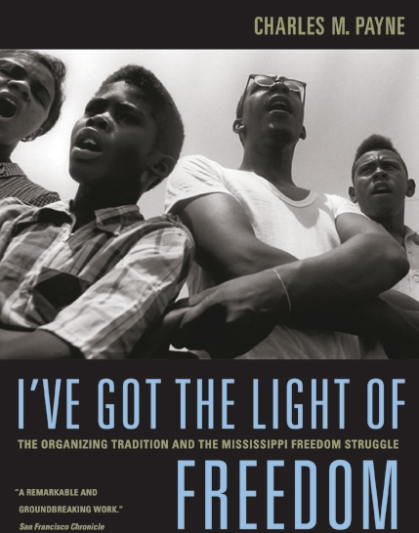

I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle presents their unsung efforts as the driving force behind the movement’s success.

“I wanted to turn the observational lens from big names to the people on the ground,’’ said Payne, professor of Africana Studies and director of the Joseph C. Cornwall Center for Metropolitan Studies.

The anniversary of his landmark study of grassroots activism was celebrated at an event held at Express Newark, featuring a conversation between Payne and Rutgers-Newark historian Melissa Cooper, author of Making Gullah, who led a fireside chat with Payne.

Cooper and others hailed the book as both a breakthrough work of history and a blueprint for today’s organizers as they fight for a more just and equitable world.

“There is so much wisdom in this book for scholars, for students, for activists, for every student who is open to the possibilities of purpose,” Cooper said, quoting from a review of the book published in the Arkansas Historical Quarterly.

Introducing Payne, School of Arts and Sciences-Newark Dean Jacqueline Mattis said the book provided a counter to the anodyne version of the civil rights movement that's prevalent today.

“In this work, Dr. Payne pushes against America’s appetite for sanitized versions of history, where the fight for civil rights is reduced to a single march, a few black and white photos, a couple of gospel songs, and a few lines from Dr. King’s speech about a dream, when the nation miraculously acknowledges the error of its ways,’’ she said.

Rather than centering male icons of the movement–such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X–Payne documented the grassroots organizing tradition that took root in Mississippi. He delved into the history of kitchen meetings, church gatherings, student canvassing and local campaigns that unfolded over years.

Payne documented the neighbors, college students, ministers and everyday people who fought and sometimes died to advance justice and freedom for all Americans.

His book challenges what he called the “individualization” of history. “This whole notion of individualization, that individual did that thing, is usually a lie,” he said. “Change is part of a social process.”

Payne was inspired to write the book during the late 1970s, when the peak of the movement and its passion had waned. He became interested in how the struggle began.

“How did the people of Mississippi have this light and fire?” he asked. “We absolutely miss what people are up against when they choose to fight. This isn’t small bravery—it’s big stuff.”

He detailed the reprisals activists faced: people shot and abused, churches bombed, jobs lost, farmers denied loans needed to plant crops, individuals refused medical care.

“I want people to understand the price that was paid by ordinary folk.,” Payne said. “This notion that the movement was a top-down thing is false—I want people to understand what everyday people risked. You could do something and they kill your child, they’re going to come burn your house down. That’s the choice you had to make,” he said.

Payne examined who was in a better position to organize the movement. These included landowning Black farmers who lived in close-knit communities and Black veterans returning from war. “They had an awful lot to do with starting the movement,’’ said Payne.He described veterans who marched in uniform past armed white men and declared, “I fought for this damn country.”

Payne interviewed parents and grandparents who refused to let white employers demean them, who would not allow white people to use terms like “auntie” or “uncle.’’

“The common thread: Even within a repressive social structure, one retains some control over one’s life,” he said.

Despite the misogyny they often faced from the movement’s leadership, women were its backbone. They took civil rights workers into their homes, canvassed, planned demonstrations, and launched voter registration drives.

“They were the foundation,’’ said Payne.

At its core, the movement drew strength from people caring for each other, said Payne.

“What is generative is a power that comes from love,” he said. “How much potential, intellectual power and social promise comes from people that we looked down on?”

As Cooper observed, “Every person has a light, something they could bring to the freedom fight.” She added, “Every person carries a little light and that’s where the movement happens.”

Asked what today’s activists might learn, Payne urged them embrace the sometimes dull and routine aspects of organizing.

“One of the things that worries me about young people who want to be a part of change—we’re all raised on these dramatic images of what social change is. They want to do something big,” he said. “They underestimate the value of the mundane.”

His advice was pragmatic: “Break off a little piece of the problem that you can do something about. You work on that with an open mind. You assume that what you can do matters.”