Photos of student thank you notes, scenes from the classroom, and visual metaphors, such as a bird's nest symbolizing resilience, show the joys and challenges faced by teachers of color are part of an exhibition at Rutgers-Newark.

Co-curated by Lynnette Mawhinney, chair of the Rutgers-Newark Department of Urban Education, along with department faculty and colleagues at Marist College, the photos were taken by teachers themselves, who share the stories behind the pictures. The exhibition lives online and is also on display at Warren Building on the Rutgers-Newark campus.

Nationwide, teachers of color comprise only 18 percent of all educators, according to Mawhinney, who specializes in research on attracting and retaining teachers of color, especially in urban schools. The project was a way to bring her academic work to life.

“I’ve never wanted to do research for research sake,” she said. “This is the teachers’ way of expressing what the job means. The ones who participated are talking to other folks and finding networks and connections. Getting people to have a dialogue is also a way teachers can be retained.”

She hopes the exhibition, which includes photos and stories from seven Black and Latinx educators in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, will help create a sense of community among the teachers, who often feel isolated, and raise public awareness of their strengths and struggles. Also curating the exhibit, in addition to Mawhinney, was Laura Porterfield, a professor of Urban Education at RU-N and colleagues Carol Rinke and Christina Fields from Marist College.

Teachers of color are “mission-driven,’’ said Mawhinney. Many want to fill a void that existed in their own classrooms or emulate a mentor who inspired them. “They say, ‘I want to be a face I didn’t have or the face that I did have. I want to show white students that folks of color can be teachers and show children of color that they can be teachers, too,’’’ she said.

The exhibition is a poignant look at their experiences, with moments of frustration offset by images representing hope, love, pride and dedication. The educators responded to five prompts, such as “What does it mean to be a teacher of color in today’s schools?” and “What sustains you?”

An image by teacher Deborah Bartley-Carter, called “Unplanned Joy,’’ which captures students playing by the ocean, shows why a spontaneous stop at the shore is emblematic for her.

“On a class trip to the aquarium, a student shared with me that they had never been to the beach. They came from a war-torn country and moved from place to place before finally arriving in America,’’ she wrote. “A small unplanned detour…turned into a teachable moment that filled our hearts with joy and kept me going just a little bit longer.”

Bartley-Carter, who has been teaching for more than 20 years and works in Jersey City, also included a more troubling image of a Latinx student sitting outside a gym filled with classmates. As punishment for refusing to read aloud, he was barred from a school dance.

“Being a teacher of color sometimes means being a witness to discipline and contradictions,’’ she wrote. “I chose this picture because the student is sitting in view of a blockade of teachers next to motivational posters that cover the doors of the gym. Punitive school cultures are uncomfortable and unhealthy for teachers and students of color.”

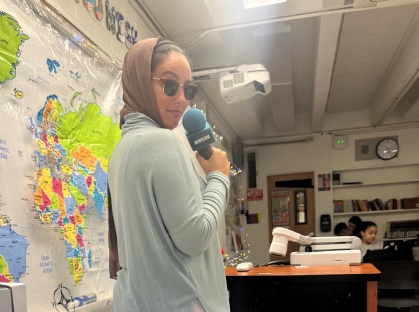

Muslim social studies teacher, Nagla Bedir, a part-time instructor in the Department of Urban Education, chose a map of Middle Eastern countries to symbolize the difficulties she navigates in the classroom.

“This image represents the content that as a teacher of color I can risk my job teaching. All of the content that, if my white co-worker taught, the response would be wildly different,’’ explained Bedir, who in 2018 founded a group called Teaching While Muslim to connect with teachers who had also been targeted because of their religion.

“If a teacher of color is teaching about people that look like them, there is this huge pressure to be "neutral" and not seem to be subjective, while that is absolutely not the reality for our white peers,'' she said.

Bedir, who teaches in Perth Amboy, also shared a photo of a student’s appreciation letter. “You are funny (kinda) and so hard working,’’ the student wrote. “I hope when you look in the mirror you see that you are more than good enough and you deserve all the happy moments that are sure to come.’’

“More than anything or anyone else in the world - it is my kids that sustain me,’’ wrote Bedir. “They reciprocate the deep love I have for them…they’ve made fun of me, sang with me, cheered me on, and just truly loved me for who I am, no matter what season of life I was in, for these last 10 years.”

As a Black woman, Mawhinney understands the value of having a teacher who looks like you. During her childhood in Sussex County, which is overwhelmingly white, none of her teachers were Black or brown.

“My early years in school in the 1980s and 1990s, I experienced blatant racism,’’ she remembered. “’The power of seeing yourself in classrooms is so important. My colleagues who had Black teachers understood themselves differently from an early age. I would have loved myself a little earlier if I had that opportunity.”

“With so many teachers of all backgrounds resigning post-COVID, the challenge of retaining teachers of color is even greater, said Mawhinney.

Bartley-Carter hopes the exhibition will foster an understanding of how teachers of color can thrive. “We need a strong supportive school climate. Feeling invisible or having to prove our self worth chips away at the core of our purpose. I hope people learn that Black and brown teachers need to feel safe, respected, and encouraged to shine each and every day that they show up for students.”

The exhibition, funded with a $50,000 grant from the Spencer Foundation, will travel to other schools and expand next year to feature additional types of school employees, including school counselors, administrators, and others in the educational field.