The nation’s ongoing epidemic of gun violence has been especially lethal for young Black men. According to the Centers for Disease Control, firearm deaths increased almost 40 percent among Black people from 2019 to 2020, to 11,904, with Black men ages 15 to 34 accounting for 38 percent of all firearm deaths. Through research and storytelling, Joseph B. Richardson Jr. has sought to tell the story of the many young men who account for these numbers.

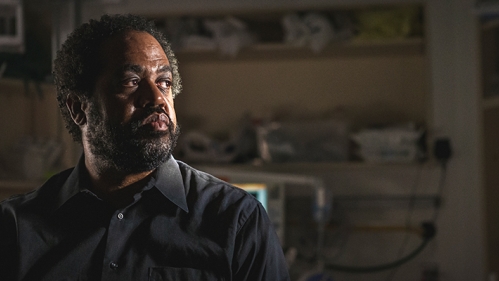

Richardson SCJ’92 GSN’03 is the Joel and Kim Feller Endowed Professor of African American Studies and Medical Anthropology at the University of Maryland and holds an M.A. and a Ph.D. from the School of Criminal Justice at Rutgers University–Newark. Building on his scholarly work in social sciences and medicine, Richardson has become a leading researcher in the effort to reduce gun violence. He is the founder and director of the University of Maryland’s Transformative Research Applied Violence and Intervention Lab (TRAVAIL), which uses a multidisciplinary approach to reduce gun violence.

This interview was part of the Rutgers School of Criminal Justice series celebrating Rutgers–Newark’s 75th anniversary. It has been edited for brevity.

Why are you doing this work?

Gun violence is the leading cause of death for young Black men between the ages of 16 and 44. African Americans are 10 times more likely to die from gun violence than white Americans, and 18 times more likely to suffer from a violent assault by a firearm. This isn’t just a criminal justice problem, but also a public health problem. It’s an epidemic in this country and has been at a crisis level for decades, and it deserves significant attention, visibility, and resources to create some effective interventions. The only way you can do that is by engaging with the health care and criminal justice systems, which is why my work intersects the two.

How did you develop TRAVAIL’s innovative approach to studying gun violence?

In 2013, I worked at the University of Maryland Prince George’s Hospital Center (now known as the University of Maryland Capital Region Health), which is a Level Two trauma center and the second busiest trauma center in the state. I used this trauma center to understand the risk factors that would bring violently injured young Black men back to the hospital for a repeat violent injury. I framed my work around the intersection of the health care system and the ways that young men involved in the criminal justice system often show up in our nation’s trauma centers. In 2017, I used my data to develop and implement a hospital-based violence prevention program (Capital Region Violence Intervention Program also known as CAP-VIP) in the trauma center. After our first year, the program was accepted into the National Network of Hospital Violence Intervention Programs, which is now called the HAVI (Healing Alliance for Violence Intervention).

I also conducted a study in Baltimore at the University of Maryland R. Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center (the state’s busiest Level I trauma center) among Black men who had been violently injured. Using secondary data analysis, I found that the number one risk factor for bringing them back to the hospital was if they had a previous history of incarceration. There are many reasons why that happens. One, we know that the impact of felony disenfranchisement for Black men has a greater effect on health and social outcomes than any other racial or ethnic group. This means once you have a felony record, it’s very difficult to get a job. You cannot live in public housing if you have a drug felony. You cannot get food stamps. You cannot get a Pell Grant or student loan (although the laws regarding this changed in 2020). So essentially, you become a second-class citizen, which forces many young men to go back to the lifestyle that resulted in their hospitalization for violent injury. This is why it’s important to pay serious attention to the ways that the criminal justice system and the health care system intersect.

There are significant traumatic and psychological effects associated with being incarcerated, which we have not thoroughly explored. If you combine the impact of felony disenfranchisement, the trauma of being incarcerated, and then having absolutely no options upon reentering society while you’re trying to survive, getting a gun and engaging in high-risk behaviors may become a means for economic survival. I don’t think people understand the complexity of that.

It’s my responsibility to show people what that looks like on the ground. Not from 30,000 feet, and not from doing drive-by research, but through immersion to understand context and the ways multiple factors within this ecosystem can alter an individual’s life trajectory.

Describe your digital storytelling project "Life After the Gunshot."

Life After the Gunshot is a manifestation of all the work that I’ve conducted ethnographically over my career. When I started my work at Prince George’s Hospital, I was interviewing young Black men, their parents, and their romantic partners. I thought it was a great time to utilize my filmmaking skills and use those interviews to show people what the lives of these young men really look like, to humanize them.

With funding from the Center for Victim Research’s Researcher 2 Practitioner Fellowship, Che Bullock, who was at the time a violence intervention specialist in my program, collaborated with me to expand the project beyond the young men we were interviewing to include all the individuals and institutions that work in a gun violence space. We started interviewing trauma surgeons, psychotherapists, violence interrupters, judges, defense attorneys, probation and parole officers, romantic partners, and parents of the young men. We brought all those stories together and made Life After the Gunshot. We premiered episode one in March 2021. It has gained a lot of traction, winning an award at the IndieFEST Film Awards in La Jolla, California. It also was a film selection for FilmFest DC and was featured on NPR’s “Here and Now.” More importantly, the film has humanized the lives of young Black men who have been shot. It gave them a platform to discuss their trauma and structural violence. It also provides a platform for them to control their narrative and insight for people to be able to relate to them on a human level.

We’re proud of the project, which can be viewed on our website and YouTube. We have some other projects that are coming soon that are not related to men but will focus on Black women in Baltimore who have been shot. We’re looking forward to uplifting the voices of Black women that have also been survivors of gun violence because their voices are rarely heard.

Click here to view the full interview with Professor Richardson.