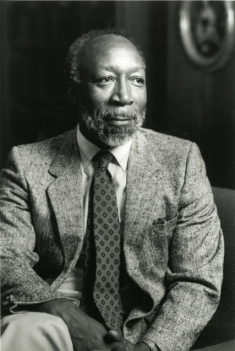

Former English Professor John A. Williams Dies at Age 89

It is with deep sadness that we announce the death of noted author and former Professor John A Williams, who taught at Rutgers University–Newark from 1979 to 1994 and whose distinguished and prolific career earned him the American Book Award Lifetime Achievement Award and induction into the National Literary Hall of Fame.

Williams died on Friday, July 3, in a veterans’ home in Paramus, N.J. He was 89. The cause was complications of Alzheimer’s disease.

Williams career spanned 30 years and multiple genres, including fiction, travel books, biographies, and picture-histories for adult and young-adult readers. He emerged onto the American literary scene in 1960 with his first novel, The Angry Ones. He caught the attention of critics a year later with his second novel, Night Song, which painted a vivid portrait of the jazz world of Greenwich Village, in New York City.

But it was his fourth work of fiction, The Man Who Cried I Am (1967), that established Williams as a major force in American and African-American literature.

A roman à clef that examined the relationship between radical African-American intellectuals and the U.S. surveillance state, The Man Who Cried I Am featured U.S. expatriates such as Chester Himes and Richard Wright, while examining 30 years of tumultuous U.S. history through the eyes of it’s protagonist, a dying black American writer living in Europe.

“Williams was one of the most original thinkers we had on American politics and, particularly, race politics,” says A. Van Jordan, the Henry Rutgers Presidential Professor at RU-N’s MFA Program in Creative Writing. “Few writers can write well about the times in which they are living. Williams was in an elite class of writers in American letters who could manage this feat.”

Williams also was a beloved teacher and colleague.

According to H. Bruce Franklin, John Cotton Dana Professor of English and American Studies at RU-N, Williams was played a key role in transforming a little-known university department into an intellectual and creative powerhouse with national and international recognition. He was also instrumental in creating both the campus’ journalism program and the foundation of what would eventually become one of the finest MFA in Creative Writing programs in the United States.

“John was, in every sense of the term, a wise man. And those qualities that made him a great writer made him an inspiring teacher and a wonderful colleague,” says Franklin. “He projected a wry humor, a sort of amused skepticism that seemed to come from profound depths of personal experience combined with deep knowledge of the human condition in our history.”

RU-N Professor of Spanish Emerita Asela Laguna remembers Williams as a “very kind, caring and serious colleague who was committed to his students, and a gentleman who spoke firmly about what he thought could be improved, but always with respect; he would never avoid bringing up race to any conversation if needed.”

John Alfred Williams was born on Dec. 5, 1925, in Jackson, Miss., and grew up in Syracuse, N.Y. He left high school to find work and in 1943 joined the Navy, serving as a medical corpsman in the Pacific.

After the war, he completed high school and attended Syracuse University on the GI Bill, where he earned degrees in Journalism and English in 1950. He credited his professors there for encouraging him to become a writer.

Unable to break into journalism after college, Williams worked a series of odd jobs, including foundry worker, supermarket vegetable clerk, and case worker for the Onondaga County welfare department. In 1955, he moved to New York City and worked as publicity director for a vanity press and as director of information for the American Committee on Africa, which supported African liberation movements.

In 1958, Williams became the European correspondent for both Ebony and Jet magazines. In the mid-1960s, he reported for Newsweek from Africa and the Middle East and from Europe for Holiday magazine. In the early 1970s, he was an editor of the periodic anthology Amistad, which was devoted to critical writing on black history and culture.

In the end, Williams became not only an insightful writer whose trenchant critiques of race in the U.S. challenged white power structures, but also a prolific one, penning 12 novels and six books of nonfiction in all.

He published works in a variety of genres, including a travel book, This Is My Country Too, (1965); a biography of Richard Wright and a controversial book on the life and death of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (both in 1970); and Africa: Her History, Lands and People Told With Pictures (1969). With his son Dennis, he wrote the biography If I Stop I’ll Die: The Comedy and Tragedy of Richard Pryor (1991). In 2003, Williams performed a spoken-word piece on Transform, an album by the rock band Powerman 5000. At the time, his son Adam was the band's guitarist.

His novels include Sissie (1963), which narrates the life of a Southern domestic worker as seen through the eyes of her two estranged children, and Sons of Darkness, Sons of Light (1969), a thriller about a civil rights activist who turns to murder after losing faith in nonviolence.

Williams also wrote the novel Captain Blackman (1972), whose influence on subsequent generations of writers is well-documented. Barbara Foley, Distinguished Professor of English at RU-N, describes the work as a sweeping transhistorical novel presenting the experiences of a single African-American soldier from the 18th century to the era of the Vietnam War.

“That novel, along with The Man Who Cried I Am, figured prominently in my attempts to theorize the relationship between history and fiction in 20th-century works of African-American literature,” says Foley.

Williams also wrote !Click Song (1982), a screed against the publishing industry and the travails that await black writers.

Over the course of his career, Williams received many professional accolades, including the American Book Award Lifetime Achievement Award and induction into the National Literary Hall of Fame. In 1995, Williams was awarded an honorary Doctor of Letters degree from Syracuse University.

Williams retired in 1994 as the Paul Robeson Distinguished Professor of English at Rutgers University–Newark.

“In John, we lost a great writer and teacher, and a generous human being,” says Franklin. “He enriched the lives of those who knew him personally and through his works. His passing is a great loss, but what he left behind is a treasure for generations to come.”

Williams, who lived in Teaneck, N.J., is survived by his wife, Lorrain; his sons, Dennis, Adam and Gregory; a sister, Helen Musick; four grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

PHOTO CREDITS (top & bottom): Courtesy of the University of Rochester