Artists Reflect on Their Work at Express Newark Opening of “Blues People” Exhibition

Nearly 500 visitors came to the opening of Express Newark’s “Blues People” exhibition, which inspired five of the nation’s leading artists to show work in dialogue with the milestone book by Newark author LeRoi Jones, later known as Amiri Baraka.

Written in 1963 and now regarded as a classic, unprecedented upon its publication, the book used the evolution of Black music in the U.S. to trace African American history and its national and global impact.

Salamishah Tillet, Express Newark’s executive director, who won a 2022 Pulitzer Prize for Criticism for her work with the New York Times, described how the book had influenced her. Tillet often focuses on art and pop culture to explore Black history and experience.

“It showed me what was possible,’’ she said.

The artist prompt for the show was “What does it mean to be Blues People in the 21st-century?” Tillet explained. Artists chose one of their pivotal works to revisit or reimagine in relation to Jones’ text.

At the opening, each artist stepped up to the microphone to share stories and reflections following a performance by Newarker Jasmine Mans, Express Newark’s first resident poet. She read a poem titled “Blues People After Amiri Baraka 2024.''

Derrick Adams--whose piece “The Holdout” combined music spun by deejay Andrea Rose Clarke, aka Sister from Another Planet, with an interview on gentrification, social commentary and art--explained the title of his work.

“Holdout is a real estate term for buildings or structures that don’t sell when everything else is being sold,’’ he said. “It represents Black culture and urban culture and how we see value that others don’t see.”

“One of the things that made me want to make art here was the spirit of Amiri Baraka,’’’ Adama Delphine Fawundu told the crowd. “I like to think about how we commit to our deep ancestry.’’

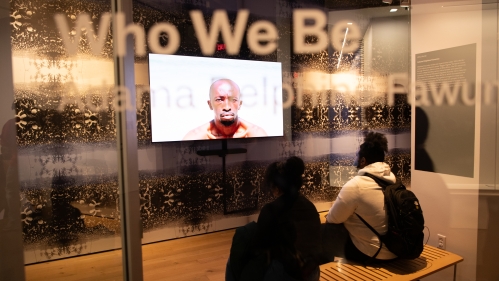

Like Jones’ book, Fawundu’s short film, “Who We Be,’’ created in 2017, draws connections between African and African-American music and culture, with a focus on sounds and images from Sierra Leone, West Africa. The walls of Box Gallery at Express Newark, where her film is shown, are lined with paper she created from repeating the image of a large crowd she photographed at a hip-hop concert on a Ghanian beach.

Adebunmi Gbadebo, who created large-scale circular textiles from Black hair, cotton, and indigo dye collected from True Blue Plantation in Fort Motte, South Carolina, where her ancestors were enslaved, spoke of the same commitment.

“I give thanks to the ancestors,’’ she said. She chose materials found at the plantation to “literally put us back into this history and this land.’'

The title of her piece, which was originally created in Newark and then reworked, is a line from Baraka’s poem “Wise, why’s, y’s”: “At the Bottom of the Atlantic Ocean There is a Railroad Made of Human Bones.’’

Newark street photographer Cesar Melgar stressed the importance of place and relationships. His series “Newark Master Plan,” black and white images of city properties that bear “Notice of Public Hearing on Proposed Development” banners, was created between 2019 and 2022.

Melgar explained, “Every ten years the city of Newark publishes a master plan to rezone and change the landscape of the city. I grew up in the Ironbound section of Newark–my mother and father are here tonight– and when I made this work, I think of people like them and myself and friends. I think of the city and how many people might not be able to live here. I think of people who are burdened by rent and by surviving. That’s what inspires me to obsessively walk around the neighborhood.’’

Photographer Accra Shepp, whose portraits of protesters during the Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter movements during the COVID-19 pandemic are part of the exhibition, asked visitors not to overlook a piece that links past and present.

“What I would like to draw people’s attention to is a black wall that recapitulates some of the anger and ideas that circulated through the violence of 1967,’’ he said, referring to the Newark uprisings of that year. It includes a well-known image on the cover of Life magazine: Joe Bass, a 12-year-old-year old Black boy, bleeding on the ground after he was shot and wounded by police. The photo is juxtaposed with the magazine’s inside cover, a white couple astride motorbikes, pouting glamorously. Other images of protestors from that era, and more recently, are also included.

“This is a way to talk about this idea of protest and activism, not as just an abstraction. People participated, this city participated,’’ said Shepp, whose installation also includes a performance art video of himself set to Baraka’s poem “We are the Blues (Funklore),’’ which Baraka recites to music by jazz artist Archie Shepp, Accra’s father and Baraka’s friend.

A pile of stamped postcards with a QR code leading to the performance invited viewers to choose a public place to listen where the piece can be heard by others and shoot a selfie or video recording the moment. The card asked where they played the video, why they chose that place, and instructed them to mail their answers to Express Newark.

By the end of the night, nearly all the cards had been scooped up.