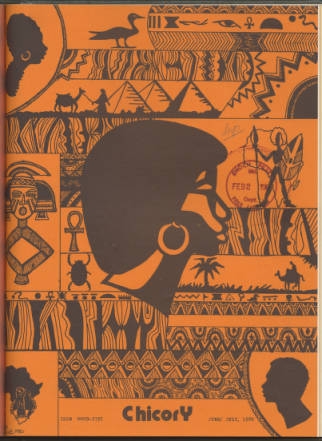

American Studies Professor Brings Forgotten Magazine Back to Life

Assistant Professor Mary Rizzo was in Baltimore in 2014, researching a book on cultural representations of that city, when she saw a reference to a 1980s magazine called Chicory, published by Baltimore’s Enoch Pratt Free Library.

Curious, she stopped by the library’s main branch to inquire. The staff had no clue about Chicory, but they dug around and eventually wheeled out boxes filled with small, mimeographed issues of the magazine that had been buried deep in their archives.

Rizzo rifled through the pages and couldn’t believe what she found: a low-budget magazine filled with poetry, prose and artwork by folks from some of Baltimore’s poorest, mostly African-American, neighborhoods addressing love, poverty, religion, black pride, gender and racial discrimination.

Published from 1966 to 1983, Chicory had long since been forgotten when Rizzo stumbled upon it. But she has partnered with Pratt to bring the publication back to life, digitizing and making it available for a new generation of readers and cultural historians on the Digital Maryland website.

“Historians and scholars have so few sources giving us insight into what regular people were thinking, and even fewer of people of color,” says Rizzo. “Chicory offers us a rare historical look inside these communities. And many of the topics it addresses are still relevant today.”

Chicory grew out of the federal Office of Economic Opportunity's Community Action Program, part of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty legislation. It was led at the local level by Evelyn Levy, who directed the Community Action Program for the library, and Thelma Bell, one of the first African-American children’s librarians at Pratt.

Levy and Bell had federal money to spend on community empowerment and hired a young local poet named Sam Cornish to visit one of East Baltimore’s neighborhood community centers and to talk to youth about an idea for a project. The kids considered making a film but opted instead to express themselves in writing after reading a memoir of a man who had grown up in the inner city.

It was there that Chicory was born, in 1966, with Cornish as its founding editor.

The library published up to 10 issues a year over the next three decades, until Chicory’s last issue in 1983. The magazine had five editors during that span.

Cornish stayed for the first three, moving on to Boston and becoming that city’s poet laureate for a time. Melvin Brown, a Chicory contributor, became the magazine’s longest-serving editor, taking over in 1971, at age 21, and helming the publication for a decade. E. Adam Jackson, a Newark, N.J., native, ran Chicory over its final three years.

These editors recruited writers through partnerships with schools and community centers, as well as word of mouth, including some who would go on to become professionals such as Baltimore Sun reporter Rafael Alvarez. Dedicated to reaching the community on its terms, they let contributors publish unfiltered, with little to no editing.

Topics ranged from drug addition, police brutality, and the 1968 Baltimore riots after Martin Luther King Jr.’s murder to the Vietnam War, crumbling neighborhoods, and love and romance. The magazine published scores of writers but was forgotten after its final issue.

In 2015, a year after rediscovering Chicory, Rizzo contacted Linda Tompkins-Baldwin, who runs the Digital Maryland project at Pratt Library, and proposed digitizing the magazine to connect with today’s readers and scholars.

“Since it was a federally funded public project run by a public library, I felt Chicory needed to be returned to the public,” says Rizzo, who serves as associate director of Public and Digital Humanities Initiatives, part of the Graduate Program in American Studies at Rutgers University–Newark. “It needed to be out there and appreciated by contemporary readers.”

Tompkins-Baldwin loved the idea. Rizzo had reached out to Brown and Cornish, now in their 70s and 80s, and they also got onboard, serving as advisers on the digitization project.

Rizzo hopes the initiative spurs a healthy dialogue with the magazine’s material, given its relevance to contemporary events. She’d like to see forums where Chicory writers talk about their experience and what it meant to them, and where Baltimore’s youth respond to their older peers’ work with writing of their own, maybe even starting a new version of the magazine themselves. She envisions using it in school settings and has begun reaching out to educators in Baltimore and other legacy cities, including Newark.

Pushing ahead with these next phases will require additional funds, however, but she has high hopes for expanding the project.

“We’re off to a good start, and the energy around this has been really positive from all quarters,” she says. “It’s too important culturally and historically not to move forward with it.”