At Express Newark Exhibition, Art Inspired by Groundbreaking Book by Leroi Jones, Later Known as Amiri Baraka

When “Blues People: Negro Music in White America” was published in 1963, Langston Hughes hailed it as “the first book on jazz by a Negro writer,’’ praising its “provocative” mix of history and sociology.

Written by Newark author Leroi Jones, who later renamed himself Amiri Baraka, “Blues People,'' now regarded as a boundary-breaking classic, used the evolution of Black music in the U.S. to trace how enslaved Africans became African-American, creating a cultural identity that changed the nation and the world.

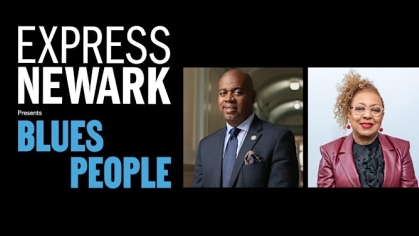

Express Newark, a socially engaged art and design center at Rutgers-Newark, will celebrate "Blues People” with an exhibition featuring some of the nation’s leading artists, whose multimedia pieces echo and expand upon the book’s central themes. The February 20th opening is part of a year-long series of events centered on Jones’ seminal book.

Five artists–Derrick Adams, Adama Delphine Fawundu, Accra Shepp, Adebunmi Gbadebo, and Cesar Melgar–were invited to re-imagine one of their pivotal works in conversation with Jones’ text. Together, they present a dialogue on art, race, resistance, class and place, all of which Jones explored in “Blues People” and throughout his career as an author and activist before his death in 2014.

In a 2013 NPR interview marking the book’s 50th anniversary, Jones, then known as Amiri Baraka, explained why he wanted “Blues People” to be regarded as more than musicology. "The book was originally titled ‘Blues: Black and White,’ he told a reporter. “But I changed it because I wanted to focus on the people that created the blues. And that was the real intent of that title: I wanted to focus on them — us — the creators of the blues.’’

“Baraka’s ability to write so beautifully and expansively about Black music is one of his greatest cultural contributions,” said Salamishah Tillet, Rutgers professor and director of Express Newark. “He recognized the power of that medium, and then used his words to capture the liberatory potential of the blues or jazz musicians' notes. Now, a new generation of artists who work in various genres are returning to this groundbreaking text to inspire new conversations about identity, history, and class today.”

Multidisciplinary artist Adams described how “Blues People” inspired him to reactivate his 2017 work “The Holdout,’’ a pyramid-like sculpture and pirate radio station that will present live guest DJ sets and music by Fela Kuti, the Fifth Dimension, Sun Ra, Bilal and Funkadelic, among others. There will also be interviews with artists and local activists about gentrification.

"Beyond the fact that Black music, like our food, fashion and vernacular, are integral to understanding our history in this country, the beginnings of Black radical thought started as conversations in very casual convenings like barbershops, church basements and living rooms,’’ said Adams. “That is the energy that ‘The Holdout’ embodies."

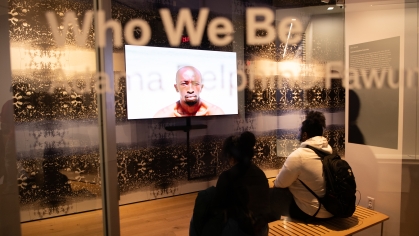

Like Jones’ book, Fawundu’s short film, “Who We Be,’’ created in 2017, draws connections between African and African-American music and culture, with a focus on sounds and images from Sierra Leone, West Africa. The walls of Box Gallery at Express Newark, where her film will be shown, are lined with paper she created from photographic transfers of Black hand gestures throughout the African diaspora.

“Amiri Baraka references the indigenous African intelligence that is subverted within the way people of African descent express themselves whether through language, music, intellect, etc,’’ said Fawundu, whose parents are from Sierra Leone. “I make works thinking about the powerful ancestral energy that exists within our bodies that shapeshifts, persists, and insists on living. It cannot be destroyed.’’

Photographer Accra Shepp said his portraits of protesters during the Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter movements embody the struggle against invisibility–a spirit that animates “Blues People,’’ he said. Shepp was moved to photograph people of color during Occupy Wall Street because the mass media overlooked them.

“Journalists and others have held the position that Occupy Wall Street was ‘white,’ that the protest was overwhelmingly young, white, and male. I was stunned when I first heard this. My experience photographing the protest was so contrary," he said. “Just as in Ellison’s ‘Invisible Man,’ these journalists literally could not see the people of color standing everywhere in their line of sight. They literally did not exist. Stupefying.”

He continued, “Amiri Baraka’s commitment to being a voice for Black America, a voice for America, entirely without a modifier and unhyphenated, was part of his practice. In my installation, I want people to feel that commitment, I want them to practice it. The installation invites the viewers to participate in being that kind of voice, to continue living the experience of “Blues People,” to go out there and be the music, be the sound.”

Shepp’s father, jazz artist Archie Shepp, was a good friend of Baraka’s and his music will be incorporated in Shepp’s installation.

Also featured in the exhibition are works by Adebunmi Gbadebo, who created large scale circular textiles from Black hair, cotton, and indigo dye collected from True Blue Plantation in Fort Motte, South Carolina, where her ancestors were enslaved, property that is now managed by a family member. The title of the piece is a line from Baraka’s poem “Wise, why’s, y’s”: “At the Bottom of the Atlantic Ocean There is a Railroad Made of Human Bones.’’

Newark street photographer Cesar Melgar will show his series “Newark Master Plan,” black and white images of city properties that bear “Notice of Public Hearing on Proposed Development” banners. The images were created between 2019 and 2022.

These are displayed alongside photos from Melgar’s 2018 “Street Views,” a series set in the Ironbound and Downtown Newark. Melgar captures how increased living costs, residential displacement, and rapid redevelopment actively threaten the vitality of Newark today, topics that are explored in Adams’ installation, which is set nearby.

Alliyah Allen, who curated the exhibition, views it as a catalyst for transformation. “These artists are our contemporary Blues People, and their works call us to action and imagine change,’’said Allen, who is Express Newark’s associate curator and program coordinator. “As a child of Newark, to be able to curate my first show at home in Baraka’s spirit of protest, ancestry, and community, is a dream come true.’’

Rutgers University - Newark, the Ford Foundation, the Andy Warhol Foundation, The HarbourView Equity Foundation, and Duggal Visual Solutions provide generous funding for this exhibition. Additional support is from New Arts Justice, Shine Portrait Studio, Paul Robeson Galleries, and Harmony Lab.