Researchers Star in a Cockroach Odyssey for the Ages

Last December—the 9th to be precise—two Rutgers University-Newark insect biologists set the world abuzz when they published an article in the Journal of Economic Entomology.

They had identified a cockroach species never before seen in the U.S. — in New York City of all places.

The news ricocheted around the Web and was picked up by an array of mainstream media outlets, including Reuters, the L.A. Times and New York Magazine. It also made it into a British paper.

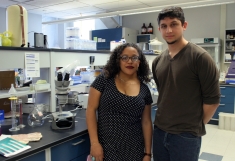

“We had no idea it would make such a splash,” says Rutgers University-Newark Biology Professor Jessica Ware, whose lab made the positive ID. “But I guess we should have, given that species was found in New York.”

Ware and Dominic Evangelista, a doctoral student working with her, confirmed the species as Periplaneta japonica, a variety native to China, Japan and southeast Russia that can survive not only indoors where its warm but also outdoors in freezing temperatures and in snow.

And while the presence of a never-before-seen species in New York City was enough to attract international attention, the story of how it landed on Evanglista’s lab bench, why he of all people was able to ID it, and who broke the news to the world are equally compelling.

That odyssey spans one-and-a-half years from the time of discovery to publication of findings and involves a cast of characters worthy of a science-thriller movie.

They include insect experts up and down the East Coast chasing after an elusive positive ID; a New Jersey–based exterminator bound to confidentiality yet trying to publicize the discovery; entomologists at the Smithsonian Institute; a University of Florida researcher whose legwork proved pivotal; and, of course, Evangelista and Ware.

In hindsight, the strands of this story might have come together anywhere. That they did so at Rutgers University-Newark makes this tale all the more remarkable.

The Long and Winding Road

In July 2012, a pest-control technician from Bell Environmental Services was doing his rounds on the High Line, an elevated walkway and park on Manhattan's West Side, when he opened up a rat-poison dispenser. What he found surprised him: several live cockroaches that looked unfamiliar, nibbling on the bait.

Enticed by the unknown and intent on solving the mystery, he gathered samples to take back to his office in Fairfield, N.J., where they landed on the desk of Ken Schumann, an entomologist and technical operations manager at Bell.

Schumann, who thought it might be a species known as the Oriental cockroach, ruled out that possibility when he noticed that both the males and females had wings. (The Oriental females lack wings.)

What he did have was an unknown roach on his hands. And that was a big deal, not only entomologically speaking but because it was an invasive species. Nevertheless, he had to stay quiet because of a non-disclosure agreement Bell had with the High Line, which is common practice between clients and their exterminators.

Soon thereafter, he showed it to his mentor Austin Frishman, one of the most prominent pest-control experts in the country. Frishman, too, was stumped.

They sent a sample to Entomology Professor Rebecca Baldwin at the University of Florida, who also was unsure of the species and passed it on to her colleague Lyle Buss, who runs the U of Florida Insect ID Lab. It was now December of the same year, and six months had passed without a positive ID.

Buss tried various ID keys—or step-by-step identification “ladders” that entomologists use to narrow the field—to no avail. He then looked at the Florida State Collection of Arthropods, a top-10 U.S. collection housed at Florida State Department of Agriculture, to get a match with specimens that had been positively identified.

Again, no match.

“Not seeing it there led me to believe it might be new to the U.S.,” says Buss, who then pivoted to a U.S. Department of Agriculture publication that identifies insects that get into food. It was there that he first encountered the name, along with diagrams, of Periplaneta Japonica.

“The male and female have different-length wings and are sexually dimorphic, or different, but the spine patterns on their legs and other features were the same,” says Buss. “I suspected it was japonica but couldn’t make a positive ID because it’s not a species in the United States. I needed confirmation.”

He contacted the Smithsonian’s Entomology Department, only to discover they no longer have a roach expert on staff. He spoke to Collections Manager David Furth, who knew exactly whom to refer Buss to: his longtime colleague and friend Jessica Ware, at Rutgers University-Newark.

Since 2011, Ware and Evangelista had made several research trips to the British Guyana rainforests with Furth and his Smithsonian team as part of the Institute’s Biodiversity in Guyana Shield Project.

“I recommended Jessica because I know her and her work on roaches and related orders of insects, and I hold her in very high regard,” says Furth.

Light at the End of the Tunnel

In January of last year, Buss reached out to Ware and emailed her photos of the species. Ware immediately turned the project over to Evangelista, who received samples from Buss shortly thereafter.

“Dominic was the perfect choice to work on this. I’m an evolutionary biologist who is interested in cockroaches, but my real focus has been on dragonflies and termites,” says Ware. “Dominic is a true expert on roaches.”

“Dominic’s one of the only people doing this work with cockroaches, combining traditional morphology with DNA barcoding and other genetic ID methods,” says Ware. “And we know the other researchers. It’s a tiny community not only in the U.S. but globally.”

So when Evangelista received the samples from Buss, he wrapped up another project as soon as he could, then got straight to work on the New York City cockroach mystery, using Buss’ work as a springboard.

Evangelista acknowledges Buss’ critical contribution, saying it helped to have a starting point because it made the DNA barcoding quicker.

“Had Lyle had no idea of the species, I would have had to get the barcode sequence for the specimen and compare it to all known cockroaches,” says Evangelista. “This way I could compare to a select few and speed up the work significantly.”

At the end of March last year, Evangelista made a preliminary ID. By the end of May, he confirmed the species. In September, the paper co-authored by Evangelista, Buss and Ware was submitted the Journal of Economic Entomology, which is published by the American Entomological Society. On December 9, the article came out and news of New York City’s newest resident went viral.

Unfinished Business

That was not the end of the story, however.

Right after Evengelista had made his preliminary ID, Ken Schumann, from Bell Environmental Services, decided to write an article for a pest-control trade magazine at the suggestion of his mentor Austin Frishman. The piece told the entire story, starting with the Bell technician’s discovery and ending with Evangelista’s positive ID. Schumann submitted it at the end of May as Evangelista positively ID’d the species.

But the magazine sat on the article—held a story that would have taken the world by storm perhaps five months earlier than it did. Schumann was incredulous.

“This was a big deal to have an invasive species in New York City. They usually appear down in places like Florida, where lots of produce gets shipped in,” says Schumann. “The magazine said they liked the piece. I was very surprised that they didn’t follow up. It was a great story for them.”

Meanwhile, Evangelista, Buss and Ware began drafting their journal article, a technical paper that was much narrower in scope and focused on the process they used to perform the positive ID.

The Rutgers University-Newark team was unaware that Schumann, an industry guy, had ambitions to publish or had submitted an article. Meanwhile, Buss had sent Schumann an early draft of his group’s manuscript, and the Bell entomologist liked their narrow scientific approach.

Nevertheless, Schumann was surprised a few months later when he realized their article would come out first. “They beat me to the punch!” he says.

Ware’s team gave credit to Schumann for discovering the species in the acknowledgments section of their article. Ware says they also would have given him an author credit had they been in direct contact with him and known he was interested in publishing.

But Schumann dismisses that idea.

“It was nice that they acknowledged my contribution, but I don’t think I should have gotten an author credit,” he says. “I didn’t participate in the DNA coding and confirmation of the species, and that’s what their article was about.”

MEDIA CONTACT: Lawrence Lerner / 973-353-1944 / lawrence.lerner@rutgers.edu